With no warning whatsoever some two thousand sardines and mackerel plunged to earth from the clouds… The fish were fresh, still with a smell of the sea about them. The fish struck people, cars, and roofs, but not, apparently, from a great height, so no serious injuries resulted. It was more shocking than anything else. A huge number of fish falling like hail from the sky – it was positively apocalyptic.

–Haruki Murakami, Kafka on the Shore

I thought of that passage this during the (now mercifully subsiding) furor over the Great Arkansan Birds Incident. Despite the maelstrom of implausible theories – fireworks, atmospheric contaminant, portent of The End of Days – nobody thought to propose that an elderly, mentally-challenged Japanese man with paranormal psychic abilities might be wandering around Arkansas conjuring plummeting animals, which honestly makes about as much sense as most of the explanations.

Sign of the Apocalypse, or the work of Nakata? Very probably neither. Courtesy of Stephen B. Thornton.

I agree with the Smithsonian bird curator who thinks that the bird kill is an arbitrary event, and not even an uncommon one, that’s become an infectious meme thanks to our innate propensity to spot patterns and events of great significance where none exist*. After the first bird kill was reported, news editors got it into their head that this was a Story, and began reporting mass animal deaths that ordinarily go undocumented. Large-scale animal kills happen, and, while I’d be the last guy to dismiss the possibility of the bird kill being anthropogenic in nature, they do happen naturally – every other day, according to federal records.

It’s ironic that the Beebe incident has us all so riled up, because things occur in nature that are a lot weirder than the so-called Aflockalypse. Even Murakami’s vision – fish falling like rain – has a basis in reality. In Honduras, in fact, it’s a regular occurrence.

Nearly every year, between May and July, the Departamento de Yoro (Honduras is divided into eighteen departments) experiences La Lluvia de Peces – the Rain of Fish.

La Lluvia begins with an intense storm: wind, torrential rain, thunder, the works. Except that after the storm clears, instead of merely puddles and rivulets, the ground is strewn with hundreds of writhing, silver fish, deposited as if by divine intervention. Joyful villagers from the town of Yoro swarm the sopping fields and collect the flopping fish in baskets. It’s apparently quite a spectacle, and so predictable that there’s even a festival organized around it.

Where my ichthyologists at? Courtesy of Atlas Obscura.

A lot weirder than the Arkansas bird kill, right? But, although there’s plenty of head-scratching and Praise-the-Lord-ing during La Lluvia de Peces (a Spanish priest claimed that he induced the fishfall by praying to god for sustenance), there are also credible scientific hypotheses that attempt to explain the piscine apparition.

First, the prevailing wisdom: the fish are sardines from the Atlantic Ocean, sucked up and deposited by a waterspout. This is the most common explanation, the one favored by the people of Yoro; and such ‘animal rain’ is actually not without precedent. But the waterspout hypothesis relies a little too heavily on coincidence: are we meant to believe that during the same months every year, a waterspout encounters and scoops up a school of sardines, and then unerringly transports it to the exact same tiny village? And that the waterspout lays down the fish so delicately that they’re evidently uninjured by the ordeal?! Impossible, maybe not; but far-fetched? Extremely.

Mmmmm... I'm skeptical. Courtesy of the Many Faces of Spaces.

The alternative explanation holds a little more water. According to a team of National Geographic researchers who visited Yoro in the 1970s, the fish are blind. This fact suggests that the fish are subterranean in origin, since by and large troglodyte species have lost the use of their eyes. The hypothesis, then, is that the heavy rains flood underground rivers and force the fish into the open through crevices in the fields. The rains occur at the end of prolonged dry seasons; so perhaps the fish, with their underground rivers drying up, are actually drawn to the surface by the sudden precipitation. This, to me, sounds a lot more plausible than a literal Fish Rain.

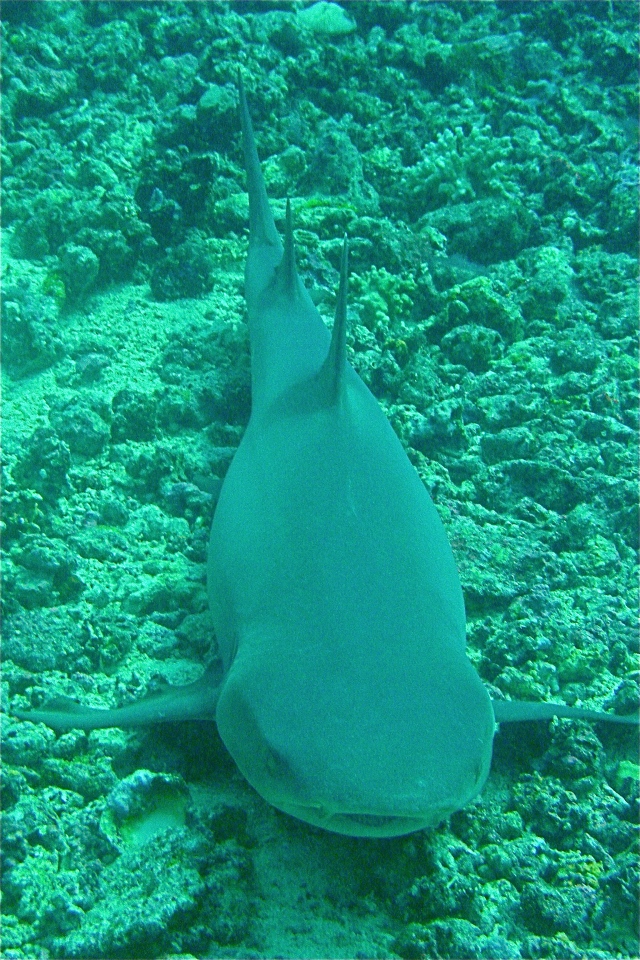

The strangest aspect is how little we know about the fish themselves. You would think that a high-profile biological mystery would be the subject of much scientific inquiry, yet La Lluvia is weirdly understudied. A National Geographic team went down to Honduras in the 70’s, yet their expedition raised more questions than it answered. No footage or photography survives (not on the Internet, anyway), and no article about the phenomenon ever appeared in the magazine. The NG team claimed that the fish were blind, thus originating the subterranean stream hypothesis; but townsfolk say that the fish have functional eyes. The NGers said the fish were a unique species previously unknown to science; the townsfolk descibre them as common, with one faction calling them sardines and another declaring them a freshwater fish.

Fish out of water. BUT HOW DID THEY GET THERE? Courtesy of The Many Faces of Spaces

About all anybody can agree on is that fish that fall (or ascend) during La Lluvia are silver, 12 to 15 cm long, and taste perceptibly different than fish procured from other sources. If they really do arise from caves, let’s hope the flavor discrepancies aren’t due to heavy metal contamination or agricultural runoff in the groundwater.

Well, so, the takeaway from all this? Nature does weird stuff all the time – stuff that’s a hell of a lot less explicable, and more fascinating, and more quasi-religious if you’re inclined in that direction, than a few birds falling out of the sky. These are dark times in many respects, and apocalypse seekers can find harbingers much more ominous than a few, quite possibly perfectly natural, fish and bird kills.

Harbingers like, say, the literally hundreds of species that go extinct every week. It’s possible that over a thousand unique species have vanished from existence since this whole Aflockalypse began. As long as we’re in the mood to wring our hands over animal deaths, let’s wring them over reefs and rainforests too, shall we? I have hope that the Aflockalypse’s impact will ultimately be positive, insofar as it forces people to confront the possibility of anthropogenic environmental destruction (an especially ironic outcome if the deaths turn out to be natural in cause).

*Footnote: The anthropologist Pascal Boyer has one of those evolutionary theories that sounds like a concocted just-so story but is pretty cool anyway: that ascribing significance in random happenstance is an evolutionary adaptation, and also the reason people believe in God. Early humans found it advantageous to overzealously detect agency – imagine, if you will, two cavemen, each of whom hears a rustle in the branches overhead. The first caveman assumes that he’s merely hearing the wind and blithely goes on foraging, but wouldn’tcha know, the rustle actually represents the stalking maneuvers of a leopard, who promptly devours the caveman, leaving behind only a stone adz for later anthropological discovery.

In such a perilous climate, Boyer theorizes, it was advantageous to spot an agent behind stimuli – the caveman who assumes that the rustle is a leopard, of course, is the one who survives. (Within reason – if you drop your basket of berries and flee every time a twig snaps, you’re at a pretty serious disadvantage, too.) That explains our contemporary reliance on religious and paranormal explanations to random events: the cognitive structures in our brains that detect agency are set to Hyperactive. Again, it’s a neat idea, but one that I’m not sure is backed by much science.

***

Big hat tip to Cephalovefor featuring FishiLeaks in this month’s Circus of the Spineless, a blog carnival about the world of invertebrates. (He even called FishiLeaks “the cleverest blog title I’ve seen in a while.” I’m sticky!)

And lastly but not leastly, I’m finally making the move to Utila Island, Honduras this week! Expect FishiLeaks posts to become more frequent, briefer, and filled with pictures from my rockin’ new camera as I advance toward DiveMastery. Also, whale sharks. Just sayin’.